How Gabriel Harvey Read His Livy

‘you doe yet keepe your selfe awake, with the delight of knowledge’

Phillip Sidney to Edward Denny (22 May 1580) in Lisa Jardine and Anthony Grafton, ‘“Studied for Action”: How Gabriel Harvey Read His Livy’, Past & Present, 129 (1990), 30-78 (39).

Lisa Jardine and Anthony Grafton’s 1990 article on the English scholar Gabriel Harvey’s annotations of Livy established a precedent which has proved valuable time and time again to the field of book history. In this important article, Jardine and Grafton reconsidered the ways in which scholars in the early modern period interacted with humanist works, proposing that not only were these figures reading with goal-orientated intent but that they were applying the information they learnt to their professional lives. Using Harvey’s heavily annotated copy of the work of the Roman historian Livy as their starting point, Jardine and Grafton identified a number of examples where Harvey’s comments indicate real-world events which had been impacted by what a person read. This allowed them to provide example after example of scholarly readers in early modern Europe literally studying for action.

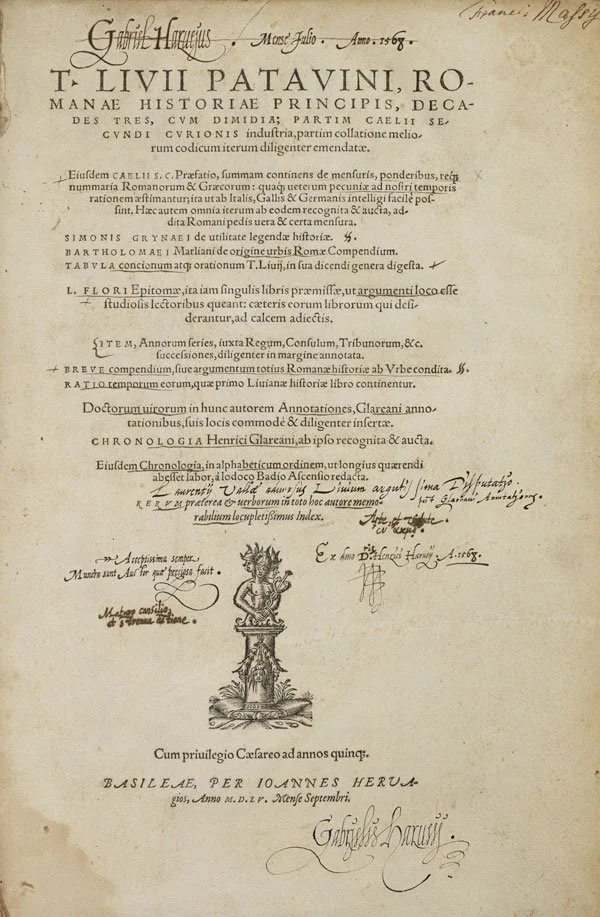

Titus Livius Patavini [Livy], T. Liuii Patauini Romanae historiae principis decades tres (Basel, 1555). Princeton University Library, Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, South East (RB) (Ex) PA6452. A2 1555q.

What set Jardine and Grafton’s piece apart from previous work was its repeated focus on ‘action’, that is, the suggestion that early modern readers were actively, rather than passively, engaging with their reading. There had long been an awareness in scholarship of marginalia in texts such as those owned by Harvey, but Jardine and Grafton went a step further. While the presence of marginal annotations in a work could, in itself, suggest that the reader was thinking about its contents, Jardine and Grafton proposed the idea that a certain kind of reader may have taken those thoughts with them into their everyday lives. For instance, they give the example of a ca. 1570 debate between Thomas Smith Jr and Sir Humphrey Gilbert (on the one side) and Thomas Smith Sr and Dr Walter Haddon (on the other) where Livy’s commentary on the military strategies of Marcellus and Fabius Maximus were discussed. In his annotations on this section of Livy, Harvey describes the people present and their perspectives on the debate. Through their scrupulous research, Jardine and Grafton trace the subsequent actions of those involved in the debate and identify that several were only months away from some form of military action. The debaters were, then, Jardine and Grafton conclude, reading Livy in a deliberate attempt to prepare themselves for the battles ahead.

Jardine and Grafton’s methodology is also significant. They use the same formula for each example they discuss which only adds to their argument. At every turn they corroborate the dates of the events in question – both the initial interaction with a text and the subsequent instances in which its ideas were influential. They identify the topics under discussion and draw comparisons between these themes and the subsequent actions of the readers. This step-by-step analysis for each example creates a line of argument which is methodical and, ultimately, wholly convincing, contributing to the article’s longevity.

‘Gabriel Harvey’, after Unknown artist, line engraving, possibly mid 17th century. NPG D27819

© National Portrait Gallery, London

Part of what makes this work so influential is the scope of its argument. Crucially, Jardine and Grafton consider the place of humanism itself in their discussion. Many early modern scholars looked towards the classical age for the foundation of their study and so considering their approaches is vital to understanding humanist scholarly practice. By framing their argument around humanist readings, Jardine and Grafton are able to go beyond their case study of Harvey and thus ensure that their argument has relevance to the wider study of early modern humanist scholarship. For example, they explore the use of the book wheel, a large rotating device used by humanist scholars to hold several volumes open at once. This allowed a reader to work with many texts without losing their place. Jardine and Grafton argue that the book wheel was more than merely a device for storing books and was used by Harvey as a carefully chosen aid to his accumulation of knowledge. In doing so, Jardine and Grafton are able to imply that early modern humanists saw reading as a key aspect of their profession, to the extent that they were actively seeking and utilising ways of improving their productivity. Consequently, Jardine and Grafton’s argument has implications beyond solely the discussion of Harvey’s work.

Continued Relevance

My PhD project concerns the early modern life of Coventry’s King Henry VIII School, founded 1545. The school had an extensive library which was opened through book donations in 1602 and was seen as a public book collection. These books, by their very nature, were intended to be read for a purpose. In sourcing their books from an academic institution, book users were choosing to read within an educational context. They expected to learn, to engage actively with what they were reading, and to use that newly gained knowledge productively. Of course, the existence of an academic library is no guarantee that its books were used productively nor that its users were thinking particularly deeply about what they were reading. However, the local community continued to donate to the King Henry VIII School library into the eighteenth century, suggesting that the library was seen to be of at least some use.

This is a different kind of studying for action to that which Jardine and Grafton discuss. In many of the examples given in this piece, Harvey reads not for academic purposes but for political, often military, ones. However, beneath this, Jardine and Grafton hint at a secondary theme in Harvey’s annotations. Throughout this article, there is a sense that the early modern figures discussed had a genuine appreciation for the benefits of reading to one’s everyday life. Just because the individuals and the context with and within which Harvey operated dealt with matters of high politics, this does not negate the relevance of this theory to more local contexts.

Conclusion

In summary, Jardine and Grafton’s article takes Gabriel Harvey’s work as a case study but does, in fact, offer a much wider commentary on what it meant for scholars to read in this period. Jardine and Grafton proposed that the entire way in which historians thought about the use of the book in the early modern period needed to be rethought and in doing so the pair reshaped book historiography. This, in combination with its continued relevance and influence, is why ‘“Studied for Action”: How Gabriel Harvey Read His Livy’ is a Key Text.

Madeleine Bracey is a PhD Candidate at the Research Centre for Arts, Memory and Communities, Coventry University.

Selected Bibliography.

Cambridge, Cambridge University Library, Add. MSS 4467-8.

Jardine, Lisa, and Anthony Grafton, ‘“Studied for Action”: How Gabriel Harvey Read His Livy’, Past & Present 129 (1990), 30-78.

18 August 2023.