Compendium Maleficarum

Key Text: Francesco Maria Guazzo, Compendium Maleficarum (Milan, 1608)

Written by the Barnabite friar Francesco Maria Guazzo, the Compendium Maleficarum was an immediate success amongst its contemporaries. First published in Milan in 1608, it was then corrected and expanded in a second edition printed by the Stamperia del Collegio Ambrosiano in 1626. An encyclopaedic survey of witchcraft and demonology, the text received the approval of the higher ecclesiastical authorities along with their permission for it to be printed (a form of approval known as the imprimatur). Yet, the Compendium has been largely overlooked by scholars and the very few studies that have addressed it have largely misunderstood its nature and aims. This post instead makes the case that the Compendium Maleficarum, one of the very last significant works on witchcraft and demonology in early-seventeenth-century Europe, is a ‘key text’ of the early modern period.

Title page to the 1608 edition. Image: University of Glasgow Library (Sp Coll Ferguson Ao-a.60).

There is little certain information about its author. We know that Guazzo (also spelled Guaccio or Guaccius) was born in the area around Milan circa 1570 and that he was an esteemed lecturer of theology from the religious order of Saint Barnaba and Saint Ambrose ad Nemus. Historians such as Montague Summers and Armando Torno have described this order as specialised in exorcism, and by the time Guazzo started writing the Compendium in the 1600s he had already been summoned to many European courts to assist in trials for witchcraft and cases of demonic possessions (including the notorious case of Duke Johann Wilhelm of Jülich-Cleves-Berg and his wife, Antonia of Lorraine, in 1605). Guazzo is also often reported as a central figure in the process against the untori, the alleged “infectors” during the plague years in Milan (1619-33), although definitive proof of Guazzo’s involvement has not yet been found. From 1607, Guazzo appears as the designated exorcist of the Leggiuno diocese, based at the hermitage Santa Caterina in Sasso Ballaro, Varese. His death seems likely to have happened around 1640. His order was dismantled and its archives lost during the following years.

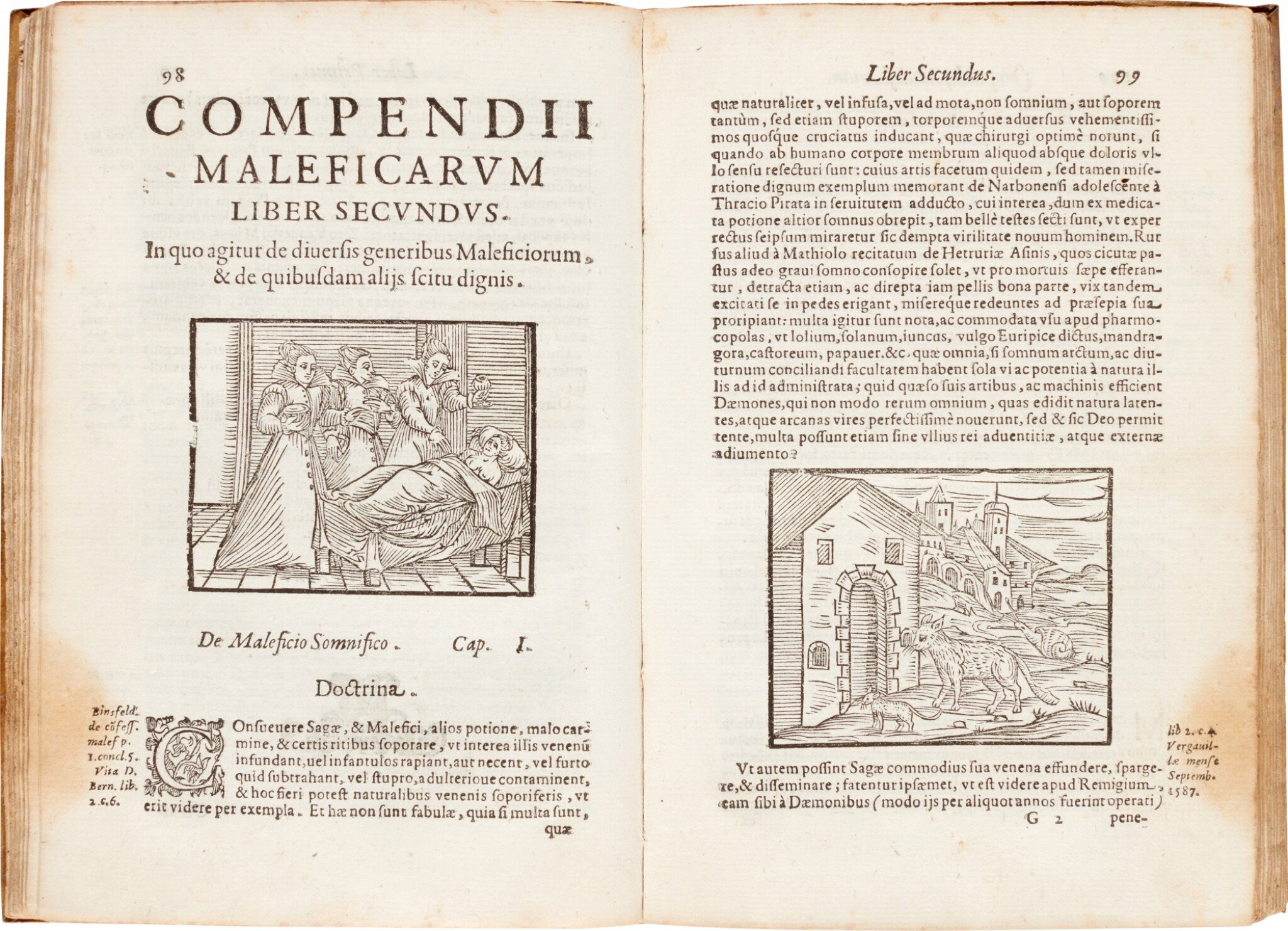

Compendium Maleficarum (in English, ‘Collection of the Evil Deeds of Witchcraft’) is an extensive description of witches’ crimes, with specific instructions on how to recognise and defend oneself against them. Organised in three books, the first edition comprises 33 original illustrations (31 woodcuts and 2 etchings), many of which are repeated, bringing the number of images across the text to forty-three in total – a number which makes the Compendium the most extensively illustrated work on witchcraft of the early modern period. The Compendium is an encyclopaedic survey of the subjects of diabolism (i.e., the adoration of the devil, resulting in the crime of witchcraft) and does not really advance any new theological position on the matter. Rather, it sums up and organises contemporary knowledge of the topic, drawing together classical authors, medieval Fathers of the Church, and more recent witchcraft treatises.

Text and woodcut illustrations from Compendium Maleficarum. Image: Glasgow University Library. (Sp Coll Ferguson Ao-a.60, p. 15).

While the Compendium is often cited, and its woodcuts are often reproduced in studies about early modern witchcraft, Guazzo’s text has not been the subject of much in-depth scholarly research. The most important contributions have been the introductions to the English (Summers, 1929) and Italian (Tamburini, 1992) translations, which are nonetheless short and increasingly outdated. Beginning as early as the 1960s, in fact, important contributions from historians and anthropologists have completely reshaped the ways in which we understand both the witch-hunts of the early modern period and the Inquisitions as two complicated, fragmented, and multi-faceted historical phenomena (see, in particular, the work of Ginzburg, Levack, Clark and Del Col). The reality of Guazzo and his text is more nuanced than Tamburini’s dismissal of the author as a ‘close-minded’ ‘bigot’ would have us believe. I believe that Guazzo’s work not only offers us valuable insights into contemporary systems of belief but can help us to better understand the Italian Inquisition, its definition and treatment of witchcraft.

In Compendium, for instance, we find a surprising element: a repeated emphasis on witches as victims of the devil. Despite his unwavering belief in the threat posed by witchcraft, Guazzo describes the witches themselves as misled victims, rather than as conscious and intentional perpetrators of evil. In many chapters, he elaborates on the numerous ways the devil abuses witches, including stealing from them, marking their flesh with his mark (‘as a brand on a fugitive slave’), and using them as instruments to carry out his evil deeds. Witches are beaten and punished, and their nocturnal gatherings (or ‘Sabbaths’) are depicted as moments of great suffering at the hands of a cruel master. Guazzo reported that ‘many repentant witches’ confessed that their sorrows were so unbearable that they thought of killing themselves just to be free again – and that the devil encouraged them to do so, so that they would also be condemned to eternal damnation. Guazzo tells us, too, that God would save the souls of those who confessed spontaneously, and this is where the Inquisition comes into the picture.

The Catholic Inquisition was often presented as a medicine, and its inquisitors described themselves as the physicians administering it. Heresies (among them, diabolism and witchcraft) were presented as a morbus animi, as the ultimate infection of the soul that needed to be treated, and heretics thus as sick people whose soul needed to be saved. This means that while the emphasis on victimhood might seem surprising, Guazzo, in line with the Roman Inquisition’s treatment of witchcraft, viewed witches as heretics suffering from an evil sickness spread by the devil and that this sickness was something that could be purged.

Text and woodcuts from 1608 edition, pp. 98-9.

The Compendium’s great corpus of illustrations also offers new perspectives on the visual culture around the prosecution of witchcraft in early modern Europe, scholarship on which has thus far mostly focused on German and English printed materials and is yet to really address their Italian counterparts. As in the famous prints by Dürer and Grien, Northern European representations of witches are gendered and extremely sexualised, presenting witches as either grotesque hags or inviting femmes fatale. In contrast, Compendium provides us with a set of prints in which not only are the women completely covered, dressed in contemporary fashion, but there are also many men in the witches’ groups, often leading the coven or having central roles in the action.

Due to the fragmented nature of most regional archives in Italy, and the consequent problems in accessing records which have often been misplaced or destroyed, it is quite difficult to give an estimate of the respective percentages of men and women accused of witchcraft in the early modern period. It is also almost impossible, at the current state of scholarship, to formulate a theory on whether gender was an important factor in the prosecution of witchcraft in Italy, and to what extent gender influenced the treatment of “witches” by the Roman Catholic Inquisition (see Herzig). Thus, rather than immediately categorising texts like Guazzo’s as the products of misogynistic and ignorant mindsets, we might pay closer attention to the rhetorical work of texts like the Compendium, whose emphasis on victimhood and use of illustrations suggests a more complicated picture. Compendium Maleficarum has been misunderstood, but it can be a ‘key text’ to help us progress in our understanding of this complicated part of European history.

Olivia Garro is a PhD Candidate and Research Rep at the Centre for Arts, Memory and Communities, Coventry University.

Selected Bibliography.

Clark, Stuart. Thinking with Demons: the idea of witchcraft in early modern Europe (Oxford, 1997).

Del Col, Andrea. ‘L’attività dell’Inquisizione nell’Italia moderna: un bilancio complessivo’, in Caccia alle streghe in Italia tra XIV e XVII secolo, (Bolzano, 2007).

Ginzburg, Carlo. Storia Notturna: una decifrazione del Sabba (Milano, 1989).

Greco, Giuseppe Grimonti. ‘Francesco Maria Guazzo’, in Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, Vol.60 (Treccani, 2003).

Herzig, Tamar. “Witchcraft Prosecutions in Italy,” in The Oxford Handbook of Witchcraft in Early Modern Europe and Colonial America, ed. Brian P. Levack (Oxford, 2013), pp. 249-67.

Levack, Brian P (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Witchcraft in Early Modern European and Colonial America (Oxford, 2013).

Summers, Rev. Montague. Compendium Maleficarum (English translation of the 1608 edition), (London, 1929).

Tamburini, Luciano (ed.). Compendium Maleficarum (Italian translation of the 1626 edition), (Torino, 1992).

Torno, Armando. Compendium Maleficarum (introduction to the Italian translation of the 1626 edition), (Milano, 2022).

11 August 2023.