Room For The Cobler of Gloucester

Key Text: Ralph Wallis, Room For The Cobler of Gloucester And His Wife With Several Cartloads of Abominable Irregular, pitiful stinking Priests (London, 1668)

In 1668, Ralph Wallis — better known by his self-bestowed moniker, the Cobbler of Gloucester — printed and distributed his last pamphlet, Room for the Cobler of Gloucester and His Wife with Several Cartloads of Abominable Irregular, Pitiful Stinking Priests. If the pamphlet itself was the metaphorical cart, then it was occupied first and foremost by Wallis and his ‘dear loving wife’, Elizabeth. Wallis structured his text as a ‘discourse’ between the two of them, one centred on stories of debauched and corrupt Church of England clergymen — the ‘several cartloads’ of ‘stinking priests’ that filled up Wallis’ literary vehicle.

Wallis’ text can be understood as the conclusion to a gleefully vitriolic nonconformist trilogy. Following Rome for Good News (c.1662) and More News from Rome (1666), Room for the Cobler continued Wallis’ attack on the Church of England and its conforming clergy as hypocritical and intolerant. A key text of its period, it not only sparks our awareness of Wallis’ forgotten yet contemporaneously well-known work, but it also tells us a great deal about religion, politics, social status, community, and family from the Civil Wars through to the Restoration and beyond.

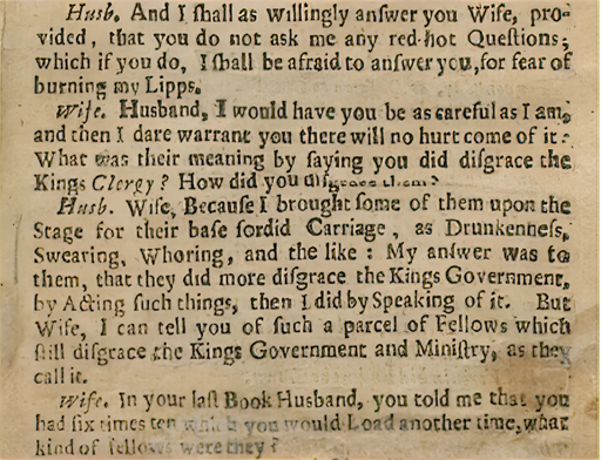

Dialogic format of Room for the Cobler (1668). Courtesy of the British Library, digitized by Google Books project.

Wallis packed Room for the Cobler full of provocative and intentionally grotesque anecdotes of clerical misconduct he had collected on his travels throughout England. Take, for example, his outlandish encounter with a minister named Mr Rowles in a Gloucester barbershop. Rowles was supposedly aware of the ridicule his fellow clergymen had received in the Cobbler’s earlier works, and asked Wallis:

not to put him in my next Book among the Deans, Doctors, and Prebends: No, said [Wallis], not I Sir, they will be ashamed of your company … [Rowles] is a frequenter of Alehouses … his Neighbours inform me, he was once foully mistaken, for being drunk, and only letting down his Breeches, he shit in his Drawers. (32–3)

With anecdotes like this, it shouldn’t come as a surprise that Wallis caused a stir in early Restoration Britain, ruffling enough feathers to be rounded up by the authorities on several occasions. Since the Licensing Act of 1662 required that press censor Roger L’Estrange approve all publications, works such as Wallis’ were either printed illegally or not at all. Wallis clearly relished being a thorn in L’Estrange’s side, and he remained a stubborn fixture of what Stephen Bardle calls the ‘Restoration literary underground’ even after being arrested, interrogated, and imprisoned in 1664.

Wallis made sure to bring up his run-ins with the law via his concerned wife:

Husband, you know that you and I have had some Discourses formerly … we thought no hurt to any, yet … you were a Prisoner first in Westminster … four Sessions you lay Prisoner in Newgate, once in Bristol, four Assizes at the Bar in Glocester. (6)

According to Wallis these hardships limited his contact with his family, a claim N. H. Keeble notes followed in the footsteps of a longstanding nonconformist literary tradition that highlighted how structural intolerance separated families and disrupted the livelihoods of humble, devout people. By referencing the difficulties he had undergone due to censorship, Wallis laid claim to a shared experience of nonconformist suffering — state-mandated persecution which would persist until the 1689 Toleration Act.

The fact that the nonconformist minister-turned-shoemaker James Forbes helped fund and circulate Wallis’ pamphlets shows that people with radical beliefs were not alone in their subversive efforts. Writing just after the 1662 Act of Uniformity and the ejection of nonconformist ministers, Wallis bemoaned the loss of dissenting leaders like Forbes in the same breath that he maligned their conformist replacements:

Let’s compare these Porrige-Priests with our Ejected Ministers, and see what a vast difference there is between them: The former guilty of all the afore-mentioned Abominations; the latter, free from all just suspicion of such things. (34)

Such sentiments were common in the Cobbler’s hometown, which boasted a deeply entrenched history of Puritanism and nonconformity. When conforming clergy took the place of dissenting ministers in Gloucester, many protested by skipping sermons in favour of attending public readings of nonconformist pamphlets like Wallis’ in public spaces.

That Wallis and Forbes each worked as cobblers/shoemakers is also significant. As Bardle puts it, ‘shoemakers were both bookish and radical’ (38), and Wallis’ occupational identity was crucial to his self-representation as a poor, simple man supported solely by the love of a good family. Cheap print commonly associated cobblers with radical religious politics thanks to prominent Puritan shoemakers such as the regicide John Hewson. However, cobblers were simultaneously known as ‘Gentlemen of the Gentle Craft’ — a phrase Wallis himself used — with the archetype of the honest shoemaker making especially frequent appearances in broadside ballads.

Late seventeenth-century ballad woodcut of a cobbler. Richard Rigby, ‘The Cobbler’s Corrant’ (c.1683–1703).

So by foregrounding his cobbler identity, Wallis intentionally engaged with the familiar seventeenth-century trope of the simple, hardworking, trustworthy shoemaker. This ‘simplicity’ might justify vulgarity, too. There is no euphemism in Wallis’ work: drunken priests like Rowles regularly ‘piss’ and ‘shit’ themselves in his endless stories of their misdeeds. Wallis could always say he was merely a truth-telling, plain-speaking labouring man, in opposition to the deceitful and hypocritical clerical elite. Room for the Cobler makes this explicit with a long list of reasons why ‘a Cobler was more honourable than a Lord Bishop’, including the pithy claim that ‘The Cobler is always mending, and making better … The Lord Bishop is always marring, and making worse’ (39–40).

Wallis certainly presented a curated image of himself for rhetorically strategic purposes, yet the glimpses his pamphlets allow into ordinary life are also their most poignant feature. It’s hard not to find it touching when Wallis’ wife recalls their first discourse ‘by the fire, as many times poor folks do’, or their second ‘when we went to bed for want of Coals and Candles’ (6). And regardless of rhetorical strategy, Wallis’ declarations of love for his wife have resulted in the memorialisation of a woman who would have been lost to history otherwise. It is important for historians of the early modern world to remember that Elizabeth Wallis was a real person, indeed, and one to whom Wallis dedicated all his works.

Dedication of Room for the Cobler (1668). Courtesy of the British Library, digitized by Google Books project.

Both the texts Wallis wrote and the literary persona he created enjoyed considerable afterlives following his death in 1669 (an event tellingly celebrated in a caustic 1670 smear pamphlet). He was an easy target for those aiming to denounce a range of nonconformist beliefs and behaviours (as in the 1704 Cobler of Gloucester Reviv’d), and he proved similarly useful for labouring perspectives looking to take up his radical mantle (see, e.g., the later Cobler of Gloucester and His Wife Joan’s New Litany). Yet, even though this cultural currency held true well into the eighteenth century, the Cobbler of Gloucester’s influence has gone regrettably overlooked. Room for the Cobler of Gloucester was not simply Ralph Wallis’ coda, but it was his most remembered work and an indisputable key text for seventeenth-century British readers — for that reason alone, it deserves to be treated by us accordingly.

Anna Pravdica is an AHRC-funded PhD Candidate in the Department of History at the University of Warwick.

Selected Bibliography.

Primary Sources

Anonymous. The Cobler of Gloucester and His Wife Joan’s New Litany (London, c.1730).

Anonymous. The Cobler of Gloucester Reviv’d (London, 1704).

Anonymous. The Life and Death of Ralph Wallis (London, 1670).

Rigby, Richard. ‘The Cobbler’s Corrant’. London, c.1683–1703. Pepys Library at Magdalene College, Pepys Ballads 4.231, EBBA 21891. http://ebba.ds.lib.ucdavis.edu/ballad/21891/image

Wallis, Ralph. Room for the Cobler of Gloucester and His Wife (London, 1668).

Wallis, Ralph. More News from Rome (London, 1666).

Wallis, Ralph. Rome for Good News (London, c.1662).

Secondary Sources

Bardle, Stephen. The Literary Underground in the 1660s: Andrew Marvell, George Wither, Ralph Wallis, and the World of Restoration Satire and Pamphleteering (Oxford, 2012).

Hailwood, Mark. ‘“The Honest Tradesman’s Honour”: Occupational and Social Identity in Seventeenth-Century England’, Transactions of the Royal Historical Society 24 (2014), pp. 79–103.

Keeble, N. H. The Literary Culture of Nonconformity in Later Seventeenth-Century England (University of Georgia, 1987).

McShane, Angela. ‘“Ne Sutor Ultra Crepidam”: Political Cobblers and Broadside Ballads in Late Seventeenth-Century England’ in Patricia Fumerton, Anita Guerrini, and Kris McAbee (Eds) Ballads and Broadsides in Britain, 1500–1800 (Routledge, 2010), pp. 207–228.

Roberts, Stephen K. ‘Wallis, Ralph [Called the Cobbler of Gloucester] (d. 1669), Pamphleteer’. Oxford Dictionary National Biography (2008).

25 August 2023.