Soundscapes

And then he drew a dial from his poke

And, looking on it with lackluster eye,

Says very wisely, ‘It is ten o'clock.

Thus we may see,’ quoth he, ‘how the world wags.

'Tis but an hour ago since it was nine,

And after one hour more ’twill be eleven.

And so from hour to hour we ripe and ripe,

And then from hour to hour we rot and rot,

And thereby hangs a tale.' When I did hear

The motley fool thus moral on the time,

My lungs began to crow like chanticleer- William Shakespeare, As You Like It (2.7.20-30).

‘My lungs began to crow like chanticleer’ … why is the motley fool’s story so funny that it would make the listener’s hearty laugh resemble the rooster from The Canterbury Tales? (That is, if we can even recognise the medieval reference!). Something about the joke simply doesn’t hold, and contemporary productions seem to agree, as this rendition from a 2013 production of the play in Cork prioritises the moment’s ‘import’ over its humour. The truth is that there is more here than meets the eye, only that it is difficult to see when we hear (or read) it in modern English. Shakespearean actor and linguist, Ben Crystal, does a remarkable job delivering the same extract in Shakespearean Original Pronunciation (OP), managing to bring to light the bawdy jokes that do not work anymore. For example, as Crystal demonstrates, in OP, ‘hour’ was pronounced the same as ‘whore’, making what seems to be a reflection about the passage of time a rather obscene joke about sex and sexually transmitted diseases (‘thereby hangs a tale’ does not quite mean ‘story’ once such original context is deciphered).

Thus, whilst soundscapes may be a contemporary term, emergent in the late 1960s, the concept is essential to our understanding of plays of the early modern period (and, indeed, to the ways we might hear many of the other keywords in this series). We may take it for granted, but plays were primarily meant to be performed on stage (not read); which means that orality is fundamental to the construction of their meanings. The phonology of early modern England — that is to say, the pronunciation system of that time — differs considerably from the way people speak English today. As Roger Lass explains, ‘[m]odern readers or playgoers are auditorily misled by their experience of Shakespeare […]. If we could be transported back to Elizabethan London and actually hear Shakespeare’s own speech, the experience would be totally different’ (Lass, 256-257). There is an important misconception, in other words, regularly held by modern audiences of Shakespeare’s plays, who are used to hearing them performed in Received Pronunciation (RP) — that is, the variation of English that tends to be associated with the BBC; a ‘prestigious’ accent. The evolution of the pronunciation of the English language has resulted in various elements of the plays, including puns, jokes, and rhymes, being lost when pronounced in contemporary English. Pronunciation was an important — but now often forgotten — device used by early modern playwrights to build characters and to invoke social, regional, and educational connotations.

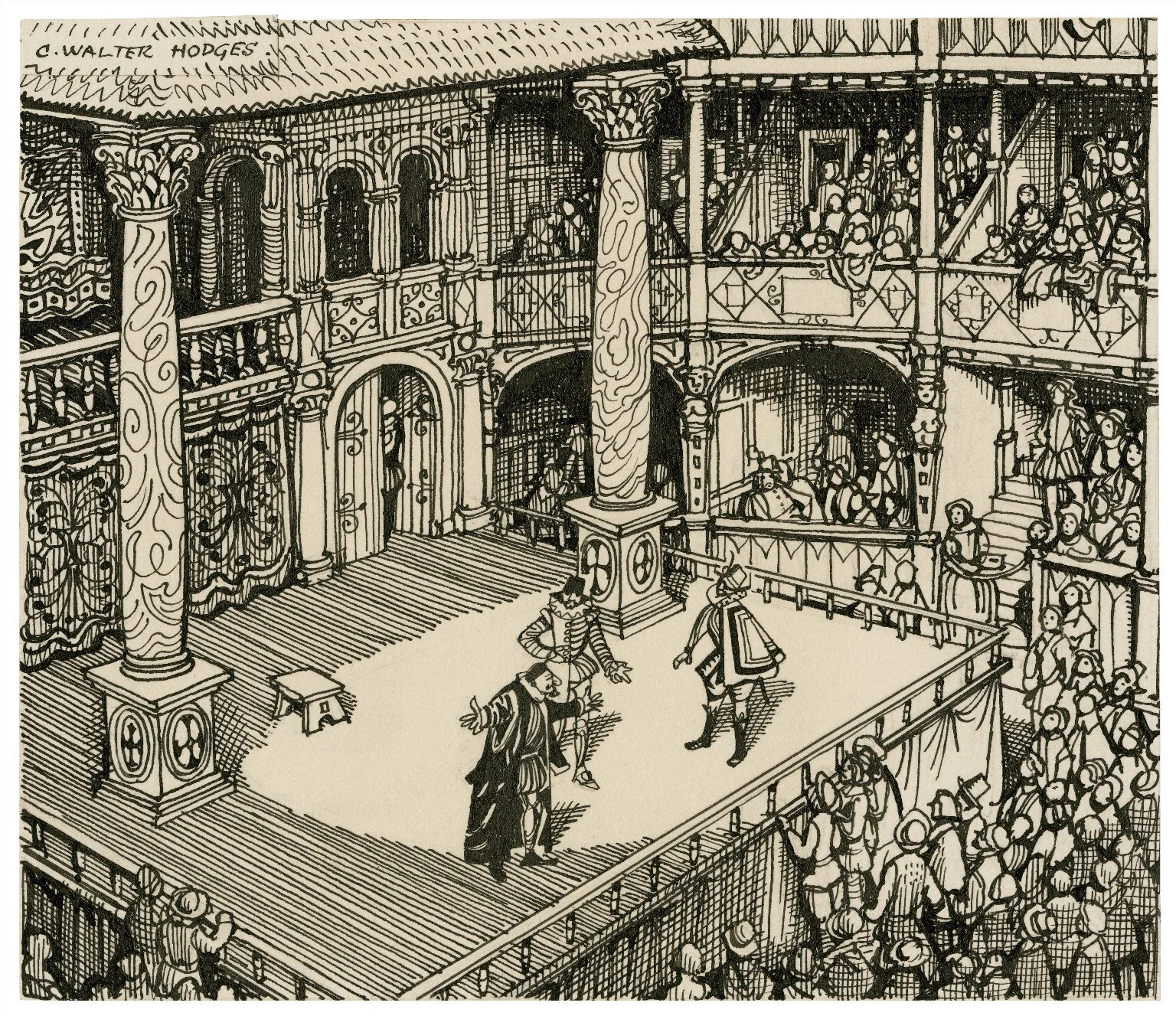

C. Walter Hodges. Illustration of the Merchant of Venice, act 1, sc. iii, being performed in an Elizabethan theatre. Folger Shakespeare Library, ART Box H688, no. 3.1 (LUNA: Folger Digital Image Collection). Licensed under Creative Commons (CC BY-SA 4.0).

The term soundscapes, in the context of drama, usually refers to sounds on stage more broadly, which can include music, sound effects (such as replicating a storm), or even noises coming from the crowds. However, when I think of soundscapes, I think much more minutely; of how each actor pronounces each vowel and consonant. I think about the wide diversity of accents that filled the early modern stages. Variation is, consequently, a key element in original pronunciation, and this variation has different manifestations.

First, there is no single version of OP. There are variants because the actors in Shakespeare’s time had very different backgrounds, like Shakespeare himself, who arrived in London from Warwickshire and would have had a mixture of accents. Second, regardless of the speaker’s particular background or accent, during the Renaissance, there was no phonetic consistency even within one person’s speech. Because the conception of language at the time was not as regulated and prescribed as it is today, people did not feel the need to be uniform with their pronunciation or to be consistent with other aspects of their personal dialect. To illustrate this, a sixteenth century Londoner had three options for pronouncing the word ‘speak’ – /spi:k, spɛ:k, spek/ – and might have chosen different versions depending on whether, for example, they meant it to rhyme with another word. And finally third, there are characters in early modern plays who are depicted as either foreigners, natives of different British regions, or as belonging to lower social backgrounds. Shakespeare provides clues (through semiphonetic spellings) of how the accents of some of these characters should be performed on stage. However, many of these clues tend to be omitted in modern editions of the texts, for the sake of ‘standardisation’.

In recent years, a lot of work has been done to promote the recovery of an ‘authentic sound’, particularly by David Crystal (a prominent linguist), who created a dictionary of Shakespearean original pronunciation and who has collaborated with his son, Ben, and Shakespeare’s Globe to put on productions in OP. However, when it comes to acknowledging the diversity of sounds that would have originally occurred on stage, this work has been done mainly by literary scholars, such as Paula Blank, Sonia Massai, and Margaret Tudeau-Clayton. The current interest in attempting (yes, attempting, because it will always be an approximation, considering that we’ll never have actual recordings of the time) to reconstruct these soundscapes is twofold: a) it helps to recover lost jokes (such as that of the motley fool, above), and b) it provides a more accurate representation of the diversity that took place in original performance, thus helping to remove current connotations of a certain brand of ‘Englishness’ that is often attached to Shakespeare. Telling actors that they don’t speak ‘Shakespeare’s English’ and, thus can’t play Shakespearean characters, is no longer a valid excuse (in fact, it never was). The importance of reconstructing the original soundscapes of early modern stages is not simply to look backwards, then, but to inform (and inspire) modern productions to embrace linguistic diversity.

Josefina Venegas Meza is a PhD Candidate in the Department of English at King’s College London.

Selected Bibliography.

Blank, Paula. Broken English: Dialects and the Politics of Language in Renaissance Writing (Routledge, 2014).

Crystal, David. The Oxford Dictionary of Original Shakespearean Pronunciation (Oxford, 2016).

---. Pronouncing Shakespeare: The Globe Experiment (Cambridge, 2005).

Lass, Roger. ‘Shakespeare’s Sounds’ in Adamson, et. al. (Eds) Reading Shakespeare’s Dramatic Language: A Guide (Arden, 2001).

Massai, Sonia. Shakespeare’s Accents (Cambridge, 2020).

Tudeau-Clayton, Margaret. ‘Shakespeare’s ‘welsch men’ and the ‘King’s English’’ in Maley and Schwyzer (Eds) Shakespeare and Wales: From the Marches to the Assembly. (Ashgate, 2010).

7 May 2021.