Refugee

While there are some instances of earlier usage, the word refugee initially gained currency in English, alongside equivalents in other major European languages such as German and Dutch, in the later seventeenth century as a means of describing Huguenot immigrants fleeing their homeland in the years surrounding the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes (1682-88). In English, the term refugee — an adaptation of the French term refugié, itself drawn from the Latin fugere ‘to flee’ — was initially exclusively associated with Huguenot migrants.

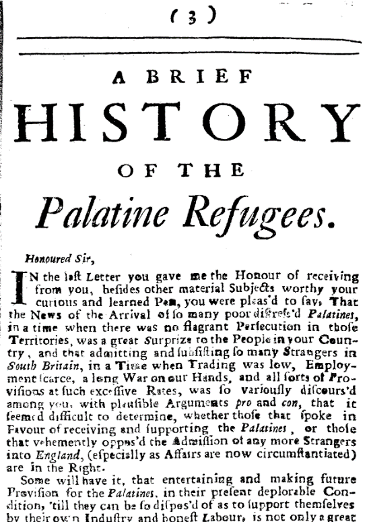

By the first decade of the 1700’s, however, use of the term was extended to refer more generally to those who had crossed borders as a result of coercion, such as the German Palatines who arrived in England seeking escape from the impact of wars and famine in the Middle Rhine region. In 1700 Daniel Defoe — sardonically feigning the tone of the overbearing xenophobe in his poem The True-Born Englishman — even depicted the historical figure of the returning King Charles II as ‘the Royal Refugeé…With Foreign Courtiers, and with Foreign Whores’.

A Brief History of the Poor Palatine Refugees, Lately Arrived in England (Dublin, 1709).

Defoe’s decision to satirise the intolerance of his compatriots highlights that the responses of locals to immigrants could vary significantly depending on their preconceptions of the ‘other’, as well as their own political sympathies and economic priorities. Such differences of opinion certainly contributed to an ambiguity surrounding the label of refugee for those early modern Europeans.

The reflections of three Huguenots in their autobiographical writings serve to vividly illustrate some of the different ways in which early modern migrants sought to position themselves in relation to the term refugee. In his Apologie (1715/16) Pierre Rival, a Huguenot pastor settled in London, lauded his former congregations as ‘Refugees like me for the cause of the pure doctrine of Christ’. For Rival, being a ‘refugee’ conferred dignity; it was a badge of pride which emphasised the bearer’s heroic suffering for the cause of ‘true Christianity’. Conversely Henri de Mirmand, a Protestant noble from Nîmes who resettled in Switzerland, was careful when writing his Mémoires to a draw a fine line between ‘our poor refugees’, as a deserving and destitute subsection of the Huguenot community in need of others’ compassion and material support, and himself, a gentleman supported by his own means. Another individual who also sought to define herself in opposition to refugees was Anne du Noyer, a former member of the provincial elites in Bas-Languedoc, who established herself as a journalist in the Netherlands. In her Mémoires, she depicted the wider body of ‘refugees’ in the United Provinces as jealous and vindictive social inferiors, seeking to despoil her of her fortune and defame her publicly. She sharply distances herself from her compatriots, scorning them as ‘people who always made or caused me distress’.

Contemporary scholars of early modern migration have shown more enthusiasm for the term refugee, deploying it as a critical lens focused upon the general dynamics and experiences which inform flight from persecution. A pattern of refugee movement that looms particularly large in the imaginations of public and scholars alike is that of large waves of migrants fleeing their homeland in a short period of time, usually in response to a common ‘push’ factor. There were several instances of these large-scale, concentrated migration waves in early modern Europe. Aside from the aforementioned 150,000 Huguenots, who for the most part made clandestine escape journeys out of France, other numerically significant examples in early modern Europe include the departure of 100,000 - 150,000 Jews from Spain who chose expulsion over conversion to Christianity (1492-3), and the 300,000 Moriscos that also opted to leave when faced with the same ultimatum a little over a century later (1609-10).

Jan Luyken, Engraving from Historie Der Gereformeerde Kerken Van Vrankryk (Amsterdam, 1686).

It would be a mistake, however, to think of these large waves as representative of early modern refugee movement more generally. Equally important were smaller groups of migrants who fled persecution in a more piecemeal manner. Exploration of some of these smaller case studies can be particularly valuable as they yield new perspectives on the challenges faced by early modern refugees. The flight of Catholics from Ireland throughout seventeenth century, in part a response to repeated English military and civil drives to reduce the ‘barbarous Irish’, underlines the way in which ethnic and religious identities were often conflated and incentivised the departure of those from targeted groups. Another key aspect of refugee experience is that separation from one’s homeland was often perceived to be temporary, a condition that could be altered by a change in political circumstances. For a fortunate minority, like the English Protestant exiles who fled from persecutions during the reign of Mary I (1553-8), changing circumstances did indeed permit return — in this case the accession to the throne of the Protestant Elizabeth I (1558). Many others, however, remained abroad and had to contend with a hankering for abandoned family, friends, material possessions, and aspects of identity fixed in a homeland to which they were uncertain they could ever return.

The concept of the ‘refugee’, therefore, offers real potential for scholars of early modern migration, in particular for underlining both commonalities and areas of significant variance in the experience of those who fled persecution in their homeland. It is nonetheless important to adopt a considered and cautious approach when deploying the term, as there are certain problems to contend with when using refugee as a paradigm.

We should be wary of the assumption that those who flee persecution can be neatly distinguished from a wider body of migrants for whom a desire for economic self-betterment underpins the decision to leave. Repression in one’s homeland is typically experienced not just as physical violence but sustained civil and social disadvantage which undermine an individual’s ability to subsist economically. Examples such as the English Pilgrim Fathers’ departure for Massachusetts (1620), or the Sephardic Jews, who in the mid-seventeenth century left various European states in order to settle in Suriname, highlight that it is not always easy to distinguish between migrants’ pursuit of physical and/or spiritual self-preservation and a desire to improve one’s material wellbeing.

It is also important to be aware of the homogenising tendency of the term refugee. If we, as the Dutch engraver Jan Luyken depicting the Huguenots above, portray refugees as a nondescript mass of victims, we can easily lose sight of the nuances of migrant experience. In the early modern period, just as today, refugees constituted a varied cast of individual actors, hailing from different socio-economic and cultural backgrounds, and motivated by their own immediate goals, psychological needs, and dreams for the future.

Dan Rafiqi is a PhD Candidate in the Department of History at King’s College London.

Selected Bibliography.

Defoe, Daniel. The True-Born Englishman A Satyr (London, 1700).

Mirmand, Henri de. Mémoires. Reprinted in Henri de Mirmand et les réfugiés de la révocation de l’Edit de Nantes, 1650-1721 (Neuchâtel, 1910).

Noyer, Anne du. Mémoires du Madame du N. (Cologne, 1710).

Rival, Pierre. Apologie de Pierre Rival, Ministre de la Chapelle Françoise au Palais de St. James (London, 1716).

5 March 2021.