Flowers

Flowers conjure up spring and rebirth, youth, beauty, freshness, and the fecundity of the natural world. In the early modern period, these associations could also apply to the female body. In printed recipe books, a best-selling genre of domestic guides, readers could find many recipes about flowers. While these miscellaneous collections included all kinds of knowledge useful in the home — from strawberry preserves to soap formulas and remedies for the plague — most flower entries were not about gardening, but about menstruation. Methods for provoking ‘red flowers’ or stopping excessive bleeding, as well as ways of treating the ‘white flowers’ (vaginal discharge), were printed in virtually all such recipe books. In a genre aimed at a wide, vernacular readership, the ubiquity of these recipes, and of the term flowers within them, can tell us much about how menstruation was understood in the period (I apologise for the unavoidable pun!).

‘Flowers’ was the most common (although by no means the only) way of referring to menstruation between the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. It has been suggested by Patricia Crawford that this usage originated in a horticultural metaphor, with menstruation as the flowers preceding the baby as fruit. This idea underpins the explanation offered by the seventeenth-century midwife Jane Sharp to her readers in 1671 — that conception was impossible without menstruation, which cleaned and emptied the womb, preparing it for the seed. The horticultural hypothesis is supported by biblical passages, such as those on how the purgation of the body was necessary to produce fruit (John 15:2).

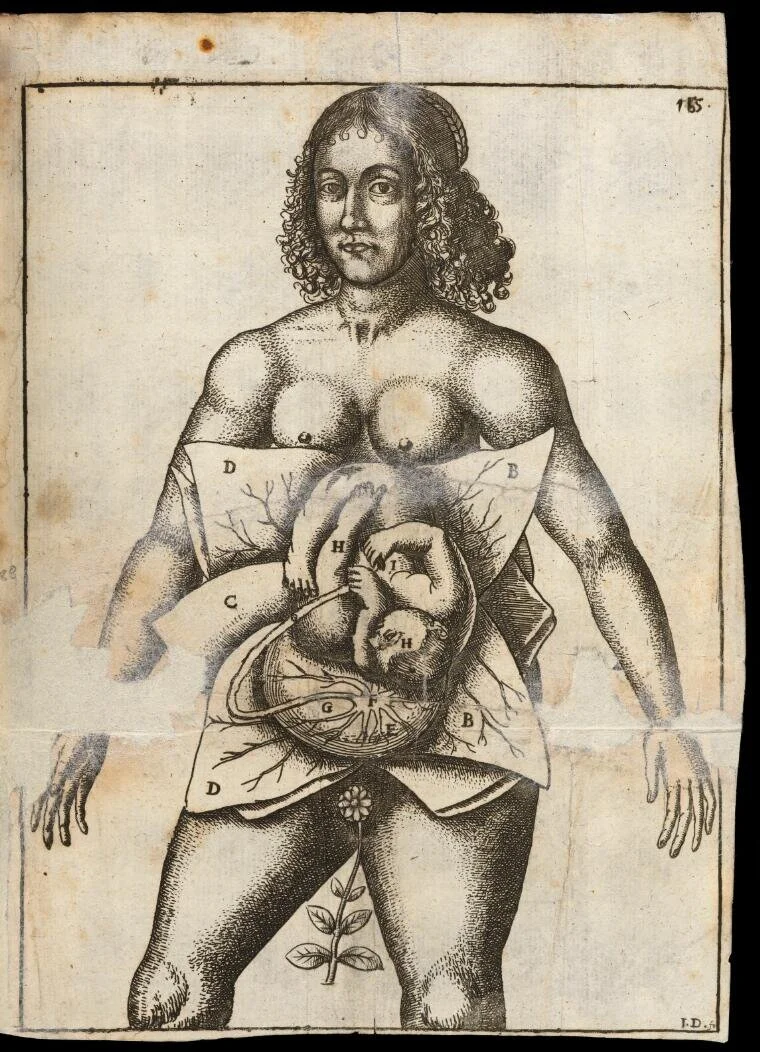

Depiction of a pregnant woman’s womb opening up like a flower in Jane Sharp’s 1671 midwifery manual.

Jane Sharp. The Midwives Book. Or the whole art of midwifery discovered. Credit: Wellcome Collection. Public Domain Mark.

The use of flowers has also been proposed as originating in a corruption of the Latin fluor or flor (‘flowings’ or ‘flux’). It is, however, more likely that flowers originated as a colloquialism used by women of Germanic origin which spread throughout Europe in the medieval period. While there are no known uses of ‘flowers’ to signify menstruation in the ancient world, either in Greek or Latin, the term became increasingly popular in most vernacular languages from the twelfth century onwards.

In early modern recipe books, the term was widely adopted, and readers could follow recipes such as ‘how to restrain the natural course [corso] of a woman if her flowers [fior] were too abundant’. It was far from the only vernacular term in use, however, and this particular Italian recipe for an ointment to be applied over the pubis to stench menstrual bleeding [menstrua] contains three different ways of referring to menstruation in just a few lines. Indeed, in most European vernaculars, menstruation was known by multiple names, which were often used interchangeably. In English, for instance, it was called ‘course’, ‘custom of women’, ‘gift’, ‘benefit of nature’, ‘terms’, ‘months’, ‘monthlies’, ‘monthly sickness’, ‘ordinaries’, ‘those’, ‘visits’, ‘time common to women’, amongst others.

In a French translation of the Italian best-seller Secrets of Don Alessio Piemontese (1589), readers could find ‘Flowers of Women’ in the table of contents. But other menstruation recipes also appeared under the heading ‘Time of Women’ and ‘For the Purgation of the Womb’. While this practice might seem confusing, with menstruation recipes spread throughout the book under different names, it could also be instructive. Readers could find the knowledge they looked for referenced to by a myriad of synonyms which would gradually teach readers new knowledge as well. The interchangeability of medical expressions can be thought of as one of the reasons why recipe books were so accessible and ‘user-friendly’: these recipes validated the vocabulary readers already had, while concurrently enriching it.

Contemporary feminist artists have embraced the floral imagery of menstruation, as in the work of Manhei Chan. © Instagram / Manhei Chan (@chanmanheyyy).

The fluidity of menstrual vocabulary also worked across languages, through translation. In the ointment recipe cited above, for instance, which demonstrated ‘how to restrain the natural course of a woman if her flowers were too abundant’ (‘A far restrenzer el corso natural di una donna se el suo fior labondasse troppo’), the term flowers is omitted in the French translation (‘Pour faire restraind(r)e le cours n(a)turel à à une femme qui l'eust trop abondant et oultre mesure’). Yet in the other menstruation recipe printed in the same book, ‘To produce her time to a woman who had it irregularly or not at all’ (‘A far produr el suo tempo a una donna che lo variasse o perdesse’), the tempo (or time) of the Italian original becomes ‘les fleurs’ (or flowers) in the French (‘Pour faire avoir les fleurs à une femme qui les eust perdues, ou qui en fust desreiglee’).

While in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries other expressions started to be used — such as ‘menstruation’ and the Greek ‘catamenia’ — flowers remained the most frequent way of referring to menstruation in Italian, German, Spanish, French, and English cheap print. The term gives a very positive idea of menstruation, which, although not the only attitude towards menstruation in the period (more ‘neutral’ expressions emphasising regularity, such as ‘terms’ or ‘règles’ in French, and more negative terms, such as ‘women’s sickness’, coexisted with the more positive ‘flowers’), was by no means a rare occurence.

Much has been written by historians about early modern perceptions of menstruation. In recipe books, women’s flowers are considered essential for fertility and for overall female health, at least in women of a childbearing age. There are even recipes in which menstrual blood (or its ‘cooked’ form, breastmilk) can be used as an active ingredient to prepare something else, usually related to reproduction. Therefore, not only were ‘flowers’ the prelude to each woman’s fruits, but a generative ingredient, marking female fecundity and physicality.

Julia Gruman Martins is a PhD Candidate in the Department of History at King’s College London.

Julia Martins writes more about 'Secrets of Women' on her website, where you can sign up to the newsletter and learn more about upcoming events and resources.

Selected Bibliography.

Anonymous. Opera Nuova Intitolata Dificio de Ricette (Venice: Giovannantonio e Fratelli da Sabbio, 1529).

Anonymous. Bastiment de Receptes (Paris: Jean Ruelle, 1560).

Piemontese, Alessio. Les Secrets du Seigneur Alexis Piemontois (Rouen: Thomas Mallard, 1589).

Sharp, Jane. The Midwives Book. Or the Whole Art of Midwifery Discovered. (London: Simon Miller, 1671).

Further Reading.

Crawford, Patricia. ‘Attitudes to Menstruation in Seventeenth-Century, England’, Past and Present, 91 (1981), pp. 47-73.

Green, Monica H.. ‘Flowers, Poison and Men: Menstruation in Medieval Western Europe’, in Andrew Shail and Gillian Howie (Eds) Menstruation: A Cultural History (Basingstoke, 2005), pp. 51–64.

McClive, Cathy. ‘Bleeding Flowers and Waning Moons: A History of Menstruation in France c. 1495-1761, PhD Dissertation’ (London: University of Warwick, 2004).

McClive, Cathy Menstruation and Procreation in Early Modern France (Farnham: Ashgate, 2015).

McClive, Cathy and Nicole Pellegrin (Eds) Femmes En Fleurs, Femmes En Corps: Sang, Santé, Sexualités, Du Moyen Age Aux Lumières (Saint-Etienne, 2010).

Read, Sara. Menstruation and the Female Body in Early Modern England (New York, 2013).

Walle, Etienne van de. ‘Flowers and Fruits: Two Thousand Years of Menstrual Regulation’, The Journal of Interdisciplinary History, 28.2 (1997), pp. 183–203.

25 June 2021.