Pin

Pins were an important and common item in early modern Britain. Readily available across society, they were used both in the household and in professional settings. Yet the proximity in which peopled lived to pins imbued these objects with dangers, from the minor discomfort caused by pricking one’s skin to potentially lethal consequences.

Pin production was a significant and lucrative industry, with sustained and reliable demand across early modern European society. Sixteenth and seventeenth century pins were typically made from brass. Wooden or bone pins had been common throughout the medieval period, but, as the prices of metal pins fell throughout the sixteenth century, brass became the dominant material. The majority of pins available in sixteenth century England were imported, with Dutch pins being particularly common, as they were more affordable than those produced domestically. Complaints were often made about the quality of these foreign items. In the seventeenth century, efforts were made to improve standards and to encourage citizens to purchase English-made pins. In 1618, James I issued a proclamation aiming to ‘encrease… the manufacture of pins’ in England. The following year, he granted privileges to the pin-makers of London, which rendered the Company the only legitimate outlet for pins in the capital and the surrounding area. Regulations around pin production remained a contentious issue throughout the seventeenth century. 1690, for example, saw particular dissatisfaction among the pin-makers of London as a result of a bill which sought to monopolise the industry. In this document, they recalled the privileges they had been granted by James and referenced the importance of securing trade from ‘the intrusion of foreigners’. Pins, then, were a politicised object viewed as an integral part of the early modern English economy.

‘Card of pins’. 1620-1650. V&A 123-1900. © Victoria & Albert Museum, London.

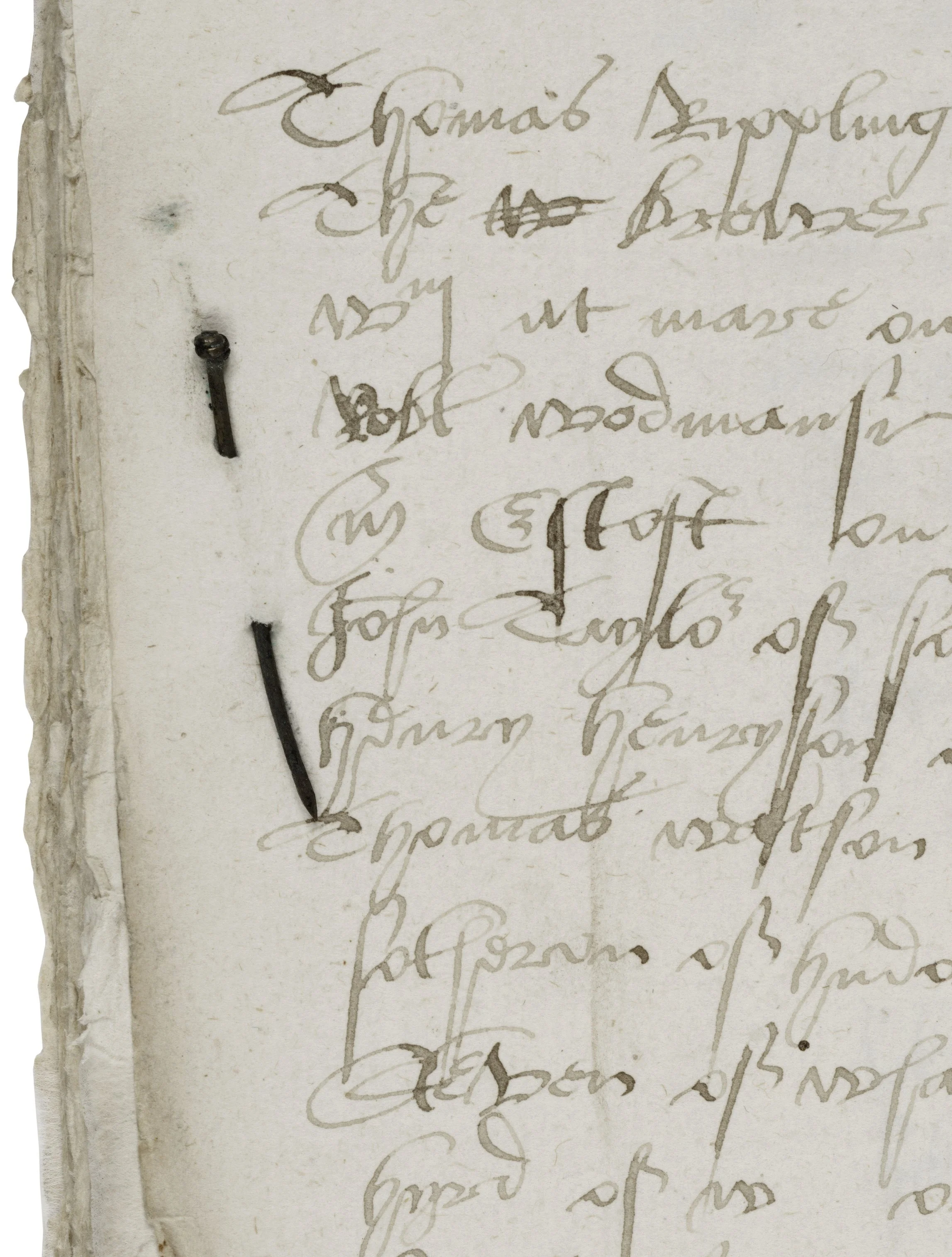

Pins were not a homogenous category. In her book Findings: The Material Culture of Needlework and Sewing, Mary Beaudry charts the range of pins, from common pins to lillikins, wig pins to lace pins. As these names suggest, pins were often used in sewing and other textile related activities in the early modern period, and were essential for the fastening of clothes and the fixing of hair. In the early modern imagination, sewing was associated with feminine virtue, and was deemed an appropriate task that would keep women from idleness and vanity. Yet even in the domestic context, pins were not the exclusive domain of women. Many men would have been proficient enough to mend clothes, and pins were also used in male attire. Beyond the domestic, pins had other important uses, too, such as securing documents together and to prick out lines in paper, examples of which can still be seen in archives today. In 1978, Joan Thirsk noted that historians had deemed pins as ‘commodities beneath notice’ (78). More recently, Beaudry has observed that items such as pins were long deemed trivial in archaeological excavations because ‘they were associated with women’s domestic activities’ (2). As their research shows, however, pins were available to and used by a variety of people in different contexts across early modern society, although they were more immediately available within the domestic context to women and girls.

‘Detail, Pin’ from fol. 21v of Anthony Smetheley, Rentals and book of reckonings (1556-1578). Folger Shakespeare Library (LUNA: Folger Digital Image Collection).

Beyond material culture and dress history, the symbolic meanings of pins have also been considered by scholars. Abigail Shinn, for example, has discussed the importance of pins to the status of one’s household; when pins and other such objects were misplaced, this represented a loss of control, and the inability to maintain one’s social standing. In the context of witchcraft, meanwhile, Diane Purkiss has discussed the vomiting of pins and other household objects, similarly arguing that this action was construed as a loss of control over the domestic sphere and a particular threat to early modern English mothers. In addition to the vomiting of pins by the ‘bewitched’, pins also featured in a variety of other magical practices, both malevolent and benevolent. Pins were imbued with a symbolic power in the early modern period and could hurt or help those who used them.

Despite, or perhaps because of, the wide availability of pins, they were considered to be dangerous objects. Being pricked by a pin appears to have been a common experience in early modern Britain. The familiarity of this type of pain likely informed the pin-prick’s recurrent use as a metaphor for other uncomfortable sensations. Richard Bovet’s Pandemonium (1684), for instance, reports the experience of an ex-school mistress living in Somerset in 1667, for whom her severe stomach pains were ‘violent prickings and pains … as if her inside had been stuck with pins, needles, or thorns’ (190-1). Pin-pricking was not only used to express physical sensations, but might also provide a metaphor for psychological feeling. Jonat Leisk, a witch accused near the end of the sixteenth century in Aberdeenshire, was described as being ‘prickit with ane giltie conscience’. The near-universal experience of being pricked by a pin likely influenced its wide use as a metaphor for various types of discomfort in the early modern period.

W. P., The History of Witches and Wizards (London, 1720), p.50. Wellcome Collection, Public Domain Mark.

Not only would pins prick, but they might also be lethal. Annie Thwaite has discussed the early modern metaphor of ‘the crooked pin in the pudding’ which she argues signified a fear of accidentally swallowing pins. Some people appear to have deliberately swallowed pins, including Joan Drake, a Buckinghamshire born gentlewoman, who experienced spiritual despair from around 1615. Among a number of attempts to take her own life, Joan ‘swallowed down many great pins, so to have dispatch’t herself’, though she was ultimately unharmed. The dangers of pins were also clearly on the minds of the friends of an unnamed gentlewoman who became possessed in 1691. The woman had been seen putting a pin into her mouth, which was promptly confiscated, out of concern that it ‘should choak her’. While no accounts survive of people being killed by swallowing pins (deliberately or accidentally), early modern people believed this to be a possibility, so much so that those who wished to take their own lives considered or even attempted doing so in this way.

For such a ubiquitous item, historians have paid relatively little attention to pins in early modern British culture and society. Throughout the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, however, pins were essential to everyday life. Pins carried a variety of meanings: they were important economic items, and their production was politicised. There use was, to a certain extent gendered, and pins could also speak symbolically and metaphorically. Early modern people lived their lives in constant proximity to pins, yet they were also wary of these objects. Understanding the meanings that the pin held can bring us closer to understanding the physical and psychological worlds of early modern British people.

Imogen Knox is a PhD candidate in the History Department at the University of Warwick.

She would like to thank Dr Ella Hawkins and Dr Annie Thwaite for their reading suggestions and advice.

Selected Bibliography.

Primary sources:

Anon, An extract of part of the Kings Majesties privileges granted to the Companie of Pinne-makers of London (London, 1619).

Anon, By the King a proclamation for the setling and encrease of the manufacture of pins in this relame (London, 1618).

Anon, The case of petition of the corporation of pin-makers, London (London, 1690).

Anon, The evil spirit cast-out (London, 1691).

Anon, The pin-makers case in opposition to Mr Killigrew’s monopolizing bill (London, 1690).

Bovet, Richard, Pandaemonium (London, 1684).

Hart, John, Trodden down strength, by the God of strength, or Mrs Drake revived (London, 1647).

Stuart, John (ed.), ‘Trials for witchcraft, 1596–1598’, Miscellany of the Spalding Club, i (1841), 82–193.

Secondary Sources:

Beaudry, Mary C., Findings: The Material Culture of Needlework and Sewing (New Haven, 2006).

Purkiss, Diane, The Witch in History: Early Modern and Twentieth-Century Representations (London, 1996).

Shinn, Abigail, ‘Cultures of Mending’, in Andrew Hadfield, Matthew Dimmock & Abigail Shinn (eds.), The Ashgate Research Companion to Popular Culture Early Modern England, (London: Ashgate, 2014).

Thirsk, Joan, Economic Policy and Projects: The Development of a Consumer Society in Early Modern England (Oxford, 1978).

Thwaite, Annie, ‘Magic and the material culture of healing in early modern England’, PhD Thesis (Cambridge, 2020), https://www.repository.cam.ac.uk/handle/1810/316485.

Friday 1 July 2022.