Mummy

In 1610, George Sandys (1578–1644), the future treasurer of the Colony of Virginia, travelled through Egypt. In the pyramids he encountered the source of a substance seen in apothecary shops throughout early modern England: mummy. That mummy was available for purchase, let alone consumption might be surprising. After all, we expect to see mummies in the British Museum but not, perhaps, in the Superdrug around the corner. Yet, before the institutional apparatus of the museum framed these ancient Egyptian bodies (many of which were acquired during British occupation) as exhibits, early modern physicians used them as a pharmaceutical. In both settings, the museum and the apothecary shop, there is a shared tension between the status of the mummy as drug/artefact (an object) and as body (a subject). In his travelogue (1615), Sandys gives a vivid account of removing the wrappings of a mummy to reveal the body — the medicine — beneath:

The linnen pulled off (in colour, and like in substance to the inward filme between the barke and the bole [the trunk of a tree]; long dried, and brittle) the body appeareth: solid, uncorrupt, and perfect in all his dimensions: whereof the musculous parts are browne of colour, some blacke, hard as stone-pitch; and hath in physicke an operation not unlike, though more soveraigne.

The corpse before him was well preserved and therefore undeniably once a person. Yet Sandys seems remarkably unperturbed by the idea of its/their cannibalistic consumption. In fact, his sole moral objection is reserved for the ‘Moores and Arabians, who make a profit of the dead, and infringe the privilege of the Sepulchers’. His qualms appear restricted to the supply of, rather than the demand for, mummy — he has remarkably little to say about the English merchants who imported the substance, the apothecaries who sold it, and the individuals who consumed it.

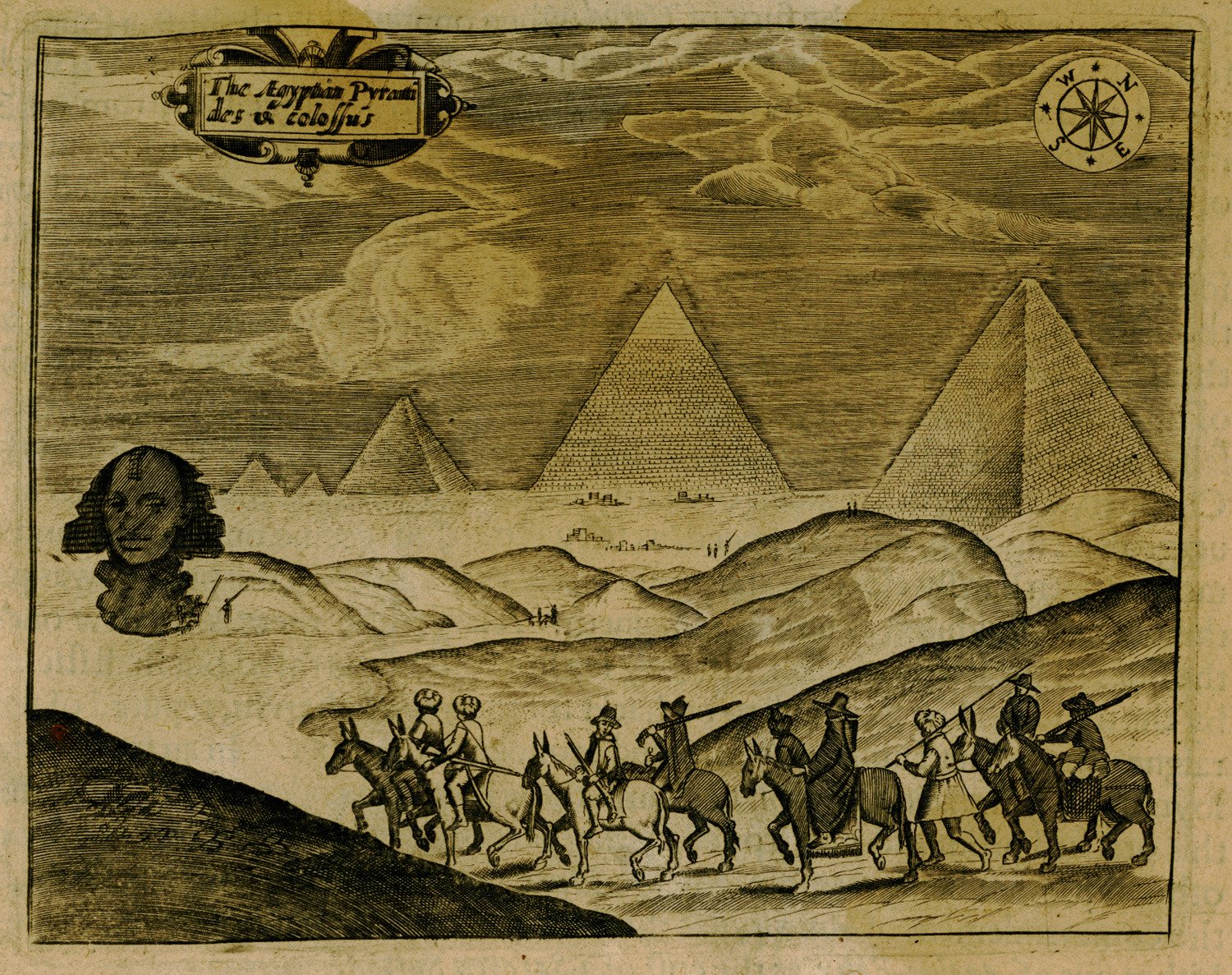

‘The Pyramids of Giza and the Sphinx’ from George Sandys, Relation of a Iourney begun An: Dom: 1610 (London, 1615). Hellenic Library - Alexander S. Onassis Public Benefit Foundation. Credit: Aikaterini Laskaridis Foundation.

Mummy was thought to have a wide range of pharmaceutical applications. In 1562, the physician William Bullein (c. 1515–1576) suggested that

Mumia [mummy] hath vertue to staunch bloud, to incarnate [heal] wounds, to help the Fallynge sycknes, beaten into a pouder and squirted wyth a syringe with Mariarum water [sea water] into the Nostrylles.

Similarly, in his posthumously published book of experiments, Sylva Sylvarum (1627), Francis Bacon (1561–1626) noted that ‘[m]ummy hath great force in Staunching of Blood’. Mummy was even put to veterinary uses in the period, George Turberville’s 1575 falconry manual recommends mummy as both a cure for a bruised hawk (‘the most ready and exquisite way to recover the hurt hawke again’) and as a means to whet a hawk’s appetite if it is not eating properly.

For those influenced by the works of the Swiss physician Paracelsus (1493–1541), the use of corpse-materials in medicine was premised upon the idea that the body of the deceased retained a residual life-force of benefit to the living consumer. Bacon, for instance, notes that the ‘Mosse, which groweth upon the Skull of a Dead Man, unburied’ has similar properties to pharmaceutical mummy, both being capable of reducing the flow of blood from an open wound. Finding a metaphorical application for mummy’s medicinal operation, Charles Fitzgeffrey sermonised to a funeral congregation, ‘[a]s Phisitians doe use to make Mummy of the Dead which serveth as a Medicine for the living; so let us make a spirituall Mummy of others Mortalitie, by turning their death into a Medicine for our life.’

Who could source and use corpse-materials and to what ends were live questions in the period. In the fourth act of Macbeth (1606), ‘[w]itches’ mummy’ is one of the ingredients thrown into the bubbling cauldron — whether this is mummy belonging to witches or mummy made from witches, we might wonder — alongside other parts of exoticised human bodies, including ‘Liver of blaspheming Jew’, ‘Nose of Turk and Tartar’s lips’. In his Daemonologie (1597), James VI of Scotland had claimed that the devil caused witches ‘to joynt [dismember] dead corpses, & to make powders thereof, mixing such other thinges there amongst, as he gives unto them’. When he acceded to the English throne and became James I of England, one of the first pieces of legislation enacted by Parliament was the 1604 Act Against Conjuration, Witchcraft and Dealing with Evil and Wicked Spirits. This Act made it a capital offence for anyone to ‘take up any dead man woman or child out of his her or their grave, or any other place where the dead bodie resteth’ or to ‘use the skin bone or any other parte of any dead person’ ‘in any manner of Witchcrafte Sorcerie Charme or Inchantment’. The use of the term ‘mummy’ by the witches in Macbeth draws our attention to the proximity of the legitimated, pharmaceutical uses of corpses in the period to their criminalised, supernatural counterparts.

Mummy consumption persisted until the eighteenth century and its decline thus neatly correlates with the ascendency of museum institutions. Egyptian bodies, over time, went from drug to exhibit, but nonetheless retained their status as a commodity for consumption. One of Hans Sloane’s (1660–1753) curiosities, which would go on to be the British Museum’s founding collection, was a mummy. As with all commodities, there is an incentive to produce counterfeits and Sloane’s mummy was no different. In 1794, writing in the Royal Society’s journal Philosophical Transactions, Johann Friedrich Blumenbach concluded that the mummy was a fake — or, we might say, a placebo.

Dan Cunniffe is a PhD candidate in the Department of English at King’s College London.

Selected Bibliography.

An Acte against Conjuration Witchcrafte and dealinge with evill and wicked Spirits (1 James I c. 12).

Bacon, Francis. Sylva Sylvarum or A Naturall History in ten Centuries (London: John Haviland and Augustine Mathewes, 1627).

Bullein, William. Bulleins Bulwake of Defence against all Sickness, Soarnesse, and Woundes that does dayly assaulte mankind (London: Thomas Marshe, 1579).

Fitzgeffrey, Charles. Death’s Sermon unto the living Delivered at the funerals of the religious ladie Philippe, late wife unto the Right Worshipful Sr. Anthonie Rous of Halton in Cornwall Knight (London: William Stansby, 1620).

James VI&I. Daemonologie in forme of a dialogue, divided into three bookes (Edinburgh: Robert Walde-grave, 1597).

Sandys, George. The Relation of a Journey begun an. Dom. 1610, in four books (London: W. Barrett, 1615).

Shakespeare, William. Macbeth. Edited by Sandra Clark and Pamela Mason. The Arden Shakespeare Third Series (London: Bloomsbury, 2015).

Some Studies of Mummy Consumption in the Early Modern Period.

Dannenfeldt, Karl H. ‘Egyptian Mumia: The Sixteenth Century Experience and Debate’, The Sixteenth Century Journal 16, no. 2 (1985), pp. 163–80.

Noble, Louise. Medicinal Cannibalism in Early Modern English Literature and Culture (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011).

Schwyzer, Philip. ‘Mummy is Become Merchandise: Literature and the Anglo-Egyptian Mummy Trade in the Seventeenth Century’ in G. Maclean (ed.) Re-Orienting the Renaissance: Cultural Exchanges with the East (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005), pp. 90-111.

Smith, Ian. ‘Othello’s Black Handkerchief’, Shakespeare Quarterly 64, no. 1 (2013), pp. 1–25.

Sugg, Richard, ‘“Good Physic but Bad Food”: Early Modern Attitudes to Medicinal Cannibalism and its Suppliers’, Social History of Medicine 19, no. 2 (2006), pp. 225–240.

3 March 2022.